I have been thinking of writing this posting since we published a positive review of Nick Lloyd's Hundred Days: The Campaign That Ended the War a few weeks ago. That book is well written and highly informative, but the focus on the "Last 100 Days" has rubbed me the wrong way since the late, and great, historian John Terraine first laid it on me in 1989.

First, it is factually wrong! It presumes, argues, or suggests that the tide of battle in the Great War was turned due to the victory east of Amiens on 8 August 1918. The turning point of the war — the beginning of the end game — indisputably, came on 15 July 1918. That was 120 days from the end of the war, not 100 (or 96 if you are counting accurately).

Second, examinations of the "Last 100 Days" tend to be heavily Anglo-centric and downplay the contributions of the other Allies, the AEF for sure, but most glaringly, the French Army. None of these comments are meant to disparage the tremendous achievement of the BEF in this period, but the French after their 1917 debacle were recovering. By the second half of 1918 they were once again mounting significant and large offensive operations, without which the broad Allied "push back" of the war's concluding days would not have been possible.

Third, the role played by most important general of 1918, Ferdinand Foch, is almost always downplayed when the "Last 100 Days" are the topic. (Nick Lloyd's work is a BIG exception to this.) It appears to me, in some cases (not all), the successes of the British Army and its commander-in-chief in this period are emphasized to bolster the arguments of "pro-Haig" elements (not without some justification) in that never ending debate over the field marshal's merits.

In his memoirs, General Ludendorff wrote that the Second Battle of the Marne had been the critical turning point in the war: "This was the first great setback for Germany. There now developed the very situation which I had endeavored to prevent. The initiative passed to the enemy. Germany's position was extremely serious. It was no longer possible to win the war in a military sense."

|

| Fighting Along the Marne, 15 July 1918 |

The battle opened with the fifth German offensive of 1918 and was followed three days later by an Allied counteroffensive, which lasted until early September. That initial defeat, in what amounted to a single day, of a German attack on a 55-mile front from Château-Thierry to east of Reims, would be the Allies' first clear victory in 1918 on the Western Front. Germany would never mount another offensive nor celebrate another victory after 15 July 1918.

Furthermore, by the date of this fifth German offensive, General Ferdinand Foch had learned to read Ludendorff's strategy. He had anticipated it and prepared his own strike against the bulge southward in the 1918 front between Soissons and Reims. As Michael Neiberg describes in his history The Second Battle of the Marne (Indiana University Press, 2007):

Mangin's Tenth Army began the second phase of the battle at 4:35 a.m. on July 18. More than 21,000 artillery pieces opened fire simultaneously on German positions. Unlike the German barrage just three days earlier, the Allied cannonade of July 18 caught their enemies completely by surprise. The first day of the Allied counteroffensive was a massive success. In total, the Allies captured 20,000 prisoners of war. One American regiment had captured 3,000 prisoners from five different German divisions, an indication of the confusion in German lines. The number of German prisoners on this first day exceeds the number of Germans taken on the first day (17,000) of the Battle of Amiens, which began on 8 August 1918, in Ludendorff's words the "black day" of the German army. A black day it surely was, but in terms of both raw number of Germans who had surrendered and the tremendous shift in momentum, July 18 was significantly more important.

|

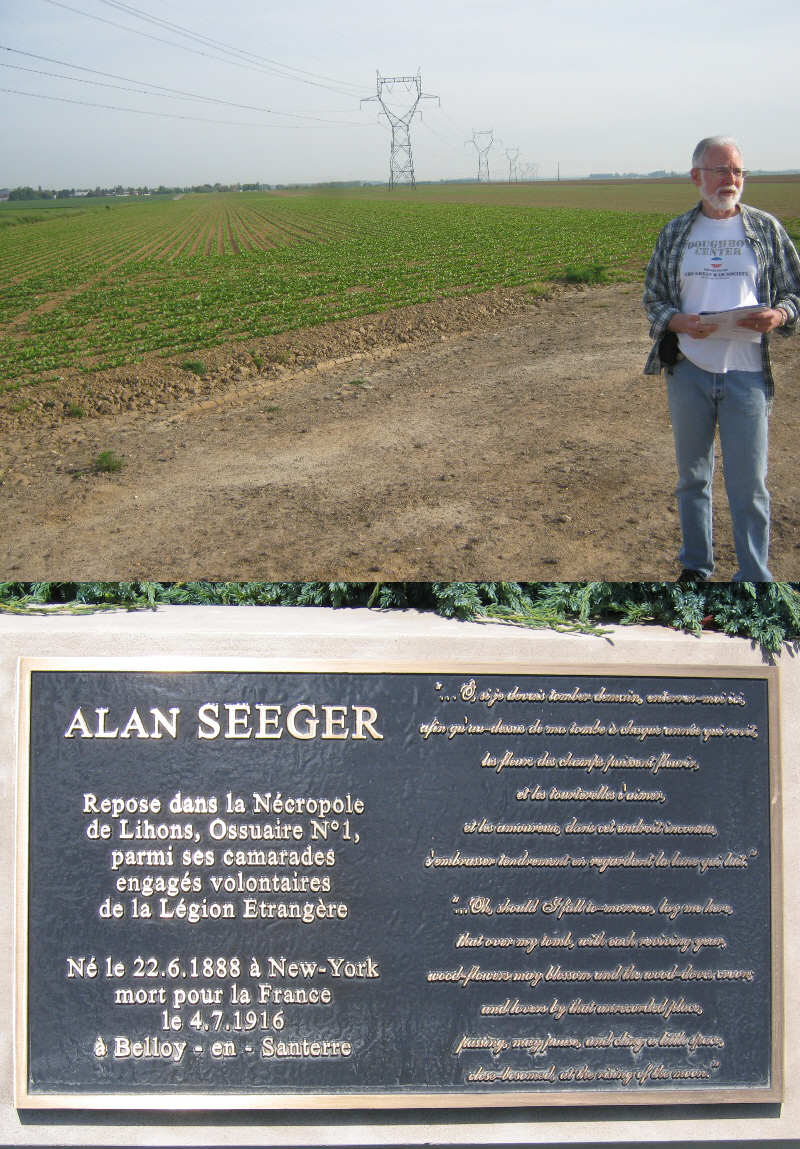

| "Les Fantomes" French Memorial for the Second Battle of the Marne |

One additional point is worth noting. The reserves that Ludendorff called upon to prevent an utter disaster in the Marne salient in July were those intended for another German offensive against the British Army in Flanders, Operation Hagen, scheduled for 1 August. Thus, had the Allies not administered the double defensive/offensive defeats of the German forces in July, the British forces would have had the Germans at their throats soon again in Flanders and very likely would not have had the freedom of action to launch their 8 August attack in the Somme sector.

In any case, I look forward to publishing someday a review of a work titled The Last 120 Days of the Great War.

This is an opinion piece by the editor, Mike Hanlon, who takes full responsibility for what is written herein.

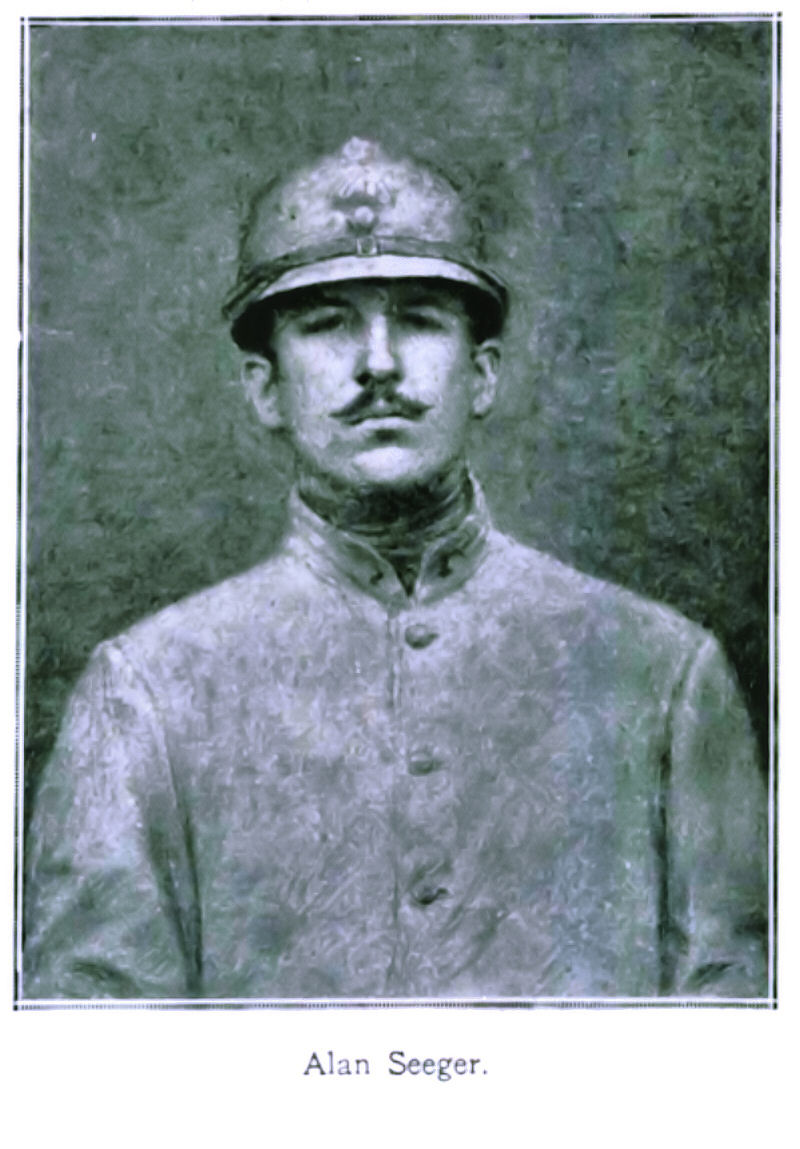

Photos from Tony Langley and Steve Miller

.jpg)