|

| Soldiers of the King's African Rifles |

The European War of August 1914 quickly spread to Africa and would soon lead to fighting throughout the continent. It would be a sideshow, but for those involved a vast and costly sideshow.

•

The war fought in Africa was fought principally by Africans themselves. Over 2,000,000 natives served as soldiers or porters; about 10 percent died in service.

•

Campaigns were instigated in North Africa by Germany and the Ottoman Empire.

•

Local rebellions were initiated or continued against colonial rule.

•

And 19th-century style campaigns were waged by the Allies against German colonies in sub-Saharan Africa – Cameroons, Togoland, Southwest, and East Africa.

•

Large numbers of colonial troops and laborers were also raised to fight elsewhere. On the Western Front 440,000 indigenous soldiers and 268,000 indigenous war workers were sent alongside 140,000 settlers of European descent between 1914 and 1918. The Armistice would end the German colonial empire and lead to a repartition of the continent.

•

Yet the First World War did not result in the upsurge of African nationalism sparked by World War II.

|

| Askaris and Bearers in East Africa |

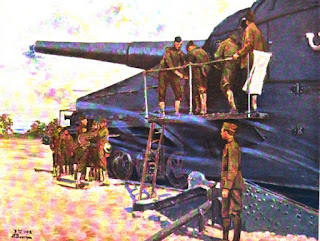

The initial impulses of the white settlers, however, had been to maintain order among the natives, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. The earliest fighting involved reducing German radio and coaling coastal stations in the name of keeping the sea lanes open.

However, both the expansionist-minded among the locals and the European governments harbored territorial aims. The German colonies, being smaller and abutting the territories of several Allied war participants seemed to be easy pickings. The Allied parties were usually the aggressors.

The war was different in Africa than in Europe:

• No modern transport. (Animals often could not be used either because of the tsetse-fly.) Human bearers made up the majority of the forces.

• No large formations.

• Little artillery.

• Disease rather than wounding was the big killer and disabler.

|

| German Troops on Parade – Probably Early in the War |

The campaign in East Africa produced one of the most admired soldiers of the war: German Col. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who tied down Allied forces ten times the size of his past the Armistice date. He returned home a hero, Berlin took a break in the revolution to welcome him.

Transport and supply were the big problems in Africa. Vast numbers of bearers were conscripted locally, usually two to three times the number of soldiers. Yet they suffered casualties at the same, sometimes higher, rates.

Disease was the big killer; besides malaria, there were blackwater fever and other exotic tropical diseases.

|

| Senegalese Troops on the Western Front |

Colonial troops from Africa were a great asset for the Allies, especially France. Take Senegal for example:

- By the end of 1918, a total of 163,000 Senegalese fiflemen were serving in French forces in the west. Tirailleur battalions served with the U.S. First Army at St. Mihiel and in the Meuse-Argonne campaign.

- The Allies — France, for example — emerged victorious in 1918 and moved quickly to improve public services in her African colonies and take advantage of the goodwill and prestige of the returning native veterans.